I thought at least five times that I probably should not write on this subject. This is such a vast and complex subject that several Ph.D could be awarded.

Then I wondered what is the point of having a personal blog if I can not even express views on topics close to my heart.

Besides doing a PhD in India has made me realize the challenges (and opportunities) of scientific research in India.

Science, especially scientific research, plays a pivotal role in the growth of any nation. I am sure you would agree that without innovation, no country can provide a better life for its citizens in the long term and, therefore, cannot be considered a developed nation.

If you look at the sheer number of scientific papers published from India, it’s immense—ranking just after the USA and China. Naturally, one would expect India to be among the top nations in terms of scientific and technological innovation.

But is that so?

Of course, we all know that’s not the case. Let’s look at some data-

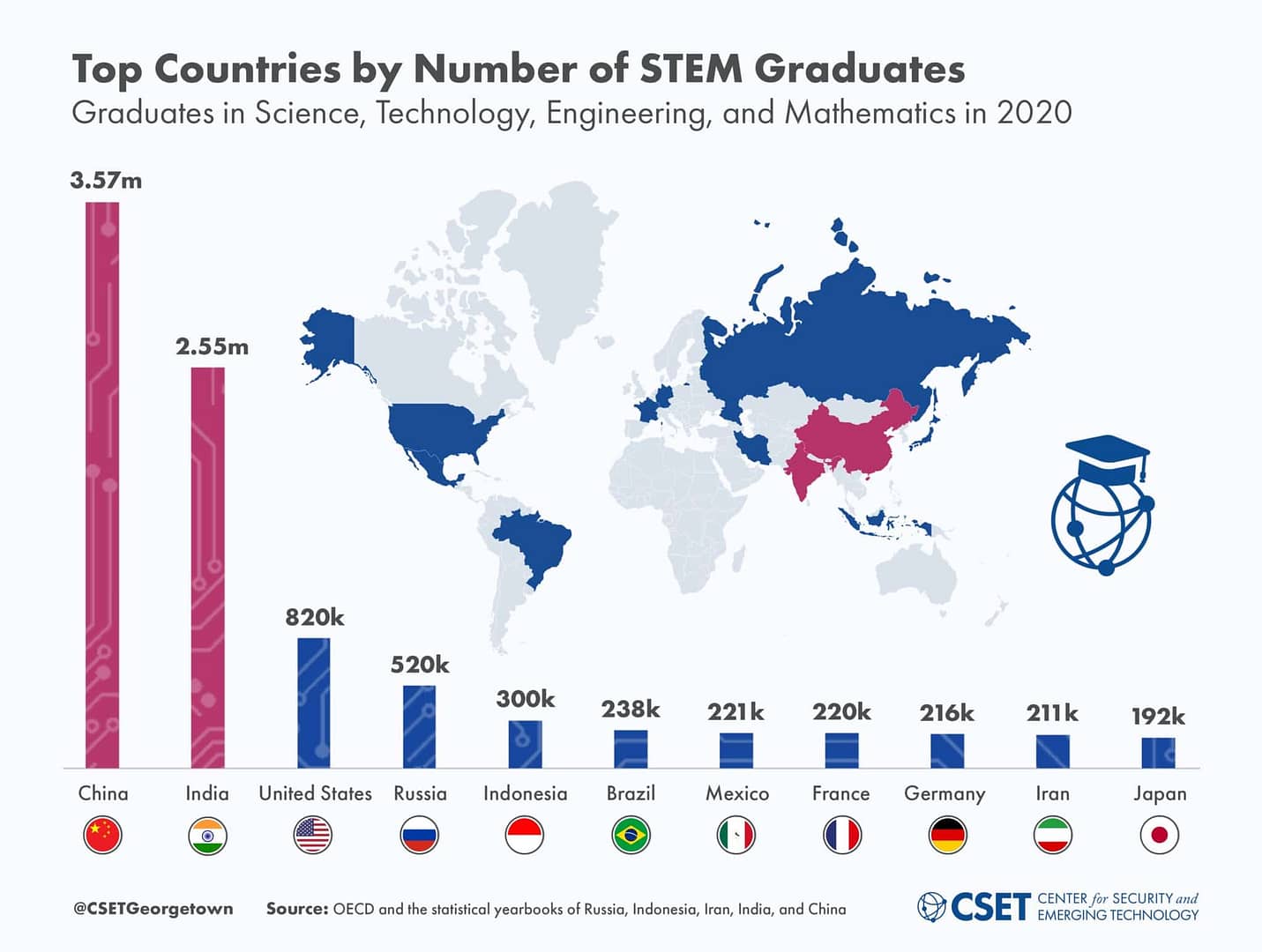

Millions of STEM graduates every year from India and China. Probably just an artifact of a larger population in these countries. India produced approximately 25,550 doctorates in 2020-21, of which 14,983 were in science and engineering disciplines. Now look at another data-

In terms of researchers (scientific or non-scientific) per million inhabitants, India’s numbers are on the lowest side, just 253. This tells you that the culture generally does not encourage or support graduates to pursue research in any field.

India has nearly 40,000 institutions of higher education and over 1,200 of these are full-fledged universities. Unfortunately, Only 1% of these engage in active research. When it comes to cutting-edge research, numbers are even worse. You can count in your hand only some IITs, IISERs, and a handful of Universities involved in globally competitive research.

Most Indian students, along with their parents, are generally very open-minded about higher education. We all know how serious Indian parents are about their children’s academics. This dedication is evident, as Indians are involved in cutting-edge fields across various industries around the world.

Then what stops India from improving its scientific performance?

It is not that the Government is not spending money (of course, it should spend way more) or is not serious about improving science. Although these are also some reasons. But more so I think is the lack of innovation culture.

The pessimistic culture of any place is shaped by multiple factors, creating a cascade effect that can hinder progress over the long term.

One of my teachers used to say ‘In India, research is a luxury, not a necessity‘.

This attitude is ingrained in people at most of the higher academic institutes (barring a few). There is a strong feeling among people (even those sitting in higher positions) that India can’t be globally competitive in scientific research.

They probably are not completely irrational. Whereas most countries striving for a better future spend at least 1-3% of their GDP on research and development (R&D), India still spends 0.6-0.7% of GDP on R&D.

Spending money is just one way. I don’t believe that increasing the budget would suddenly fix all the problems. It’s just a crucial screw that should be tightened but can’t fix the whole system.

The most pivotal aspect that needs refinement is the belief system—the mindset that important research can be conducted from India. While several positive works have been done and are ongoing, in a country of 1.4 billion people, both the world and Indians themselves expect at least ten times more.

Changing a culture is never easy, there is a lot of resistance. But a better future is hardly possible without becoming a scientific powerhouse.

We should not just blame the government or institutions; a culture becomes prevalent through the collective actions and attitudes of everyone within a society.

Whereas everyone seems to see only the government’s side of the faults (which are valid) like increasing the budget, improving infrastructure, granting institutional autonomy, streamlining research funding and disbursements, bringing recruitment flexibility, creating funding stability, etc., the people especially students (and supervisors) are also responsible for creating the not so great research culture.

We must come out of the mindset of ‘research is a luxury‘ to ‘research is a necessity‘.

Jumping into research solely for the monthly fellowship, rather than out of curiosity, is a waste of resources for everyone. The prestige of obtaining a doctorate is also often too tempting for some students to resist (Prestige should never be the reason for joining a doctorate).

As students, we must ask ourselves, ‘Why pursue research despite all the uncertainties?’

A reasonable answer to that must be figured out before joining a research program for longer periods. Quality control should be of utmost importance in academic institutions. The number of retractions, data fabrication, and paid journal papers is constantly rising in India. A strict regulatory body should monitor scientific misconduct.

One of the most grueling downsides of the research program that often goes overlooked is the availability of jobs after a PhD or postdoc. This is not just India-specific but true for the entire world. While every country likes to put a bigger number when it comes to doctorates it has produced, nobody seems much interested in publishing data on how many of their doctorates end up having good professional careers.

The supply of doctorates has exceeded the demand. Less than 1% of doctorates secure positions in academic institutions. Although the state of industries in India has improved, they still cannot recruit a significant number of doctorates and are often reluctant to hire them, as recruiting postgraduates saves money.

Regarding other sectors like finance, media, and law there are only scarce opportunities for doctorates, and even if there are some, most Indian doctorates are unaware of them.

This is where the government can do significantly better by providing incentives and creating better opportunities for doctorates (with good research profiles) in different sectors. After all, why a doctorate should only dream of becoming a professor or Industry expert?

The training of a doctorate should be of value in any sector, be it finance, law, media, business, or something else.

If you look at human history, you’ll find that the primary reason Homo sapiens triumphed over other species is their ability to work in a team and innovate constantly.

It is just innate human nature to explore, to find the unknown. How else would we progress without exploring the unknown?

A bigger economy definitely helps to build better infrastructure, but without a progressive and positive culture, becoming an innovative country is hardly possible.

The responsibility lies not only with the government but also with big industries, academic institutions, faculties working in institutes, and students working in labs.

While it’s easy to blame the system and others, it is much more worthwhile to focus on the positive aspects and strive to achieve better scientific outcomes from India. I know for sure that many people are doing great work (in India) and paving the way for young researchers.

I remain optimistic that India will become bigger and better in science over time. After all, this is the civilization that has gifted the world with numerous fascinating inventions.

As Sri Aurobindo once said-

India of the ages is not dead nor has she spoken her last creative word; she lives and has still something to do for herself and the human peoples.